Risk Management

This section of the Manual provides guidance on risk management in the context of Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (Global Fund) grants. Though this guidance focuses primarily on UNDP-implemented Global Fund grants, provisions may be of relevance to any Principal Recipient. The section starts with some basic concepts of risk management, which may be familiar to some readers. Please click ‘next’ or select the desired topic from the left-hand menu.

The Risk Management section of the Manual is not a substitute for the application of UNDP’s Programme and Project Management (POPP) throughout the project cycle. This section should be read as an additional guidance to POPP, for quality and risk-informed programming.

Introduction to Risk Management

Why Risk Management?

A ‘risk’ is defined as the effect of uncertainty on organisational objectives, which could be either positive and/or negative (ISO 31000:2018 see Appendix 1, of UNDP Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) policy for all terms and definitions).

On the other hand, an ‘issue’ is an unplanned event that has already happened and is currently having an impact on the project’s success. An issue is certain, it is happening in the present, and it needs immediate attention. Issues are managed through an issue register, while risks are mapped and managed through a risk register, as we will see in the following sections.

Risk management is a set of coordinated activities undertaken with the aim to identify and control the level of risks and their effects on organisational objectives. Risk management is a central component of project management and is integrated throughout the project cycle. Risk management focuses on exploring opportunities and avoiding negative consequences within the realisation of UNDP Strategy.

In risk management, risk treatments or controls are specific measures put in place to modify the risk exposure, by reducing the likelihood or the impact of a risk event. The Risk Manager is a designated person responsible for facilitating and coordinating the management of risks. The Risk Owner is the person with the ultimate accountability and authority to ensure that a risk is managed appropriately. At the project level, this is often the project manager. While a Risk Treatment Owner is the person assigned with the responsibility to ensure that a specific risk treatment is implemented.

Assurance is an independent check and verification to confirm whether risk management is being implemented as intended and delivering the expected benefits.

In project management, every project is subject to three constraints: scope (products), time (schedule), and cost (budget). Overall project quality and success depend on the ability to ensure a balance between these three constraints. Risk management is a process that enables the project manager to have information for prompt detection and management of risks to minimise the impact on project constraints.

Practice

Pointer

Practice

Pointer

In development projects, quality results are those able to meet organisational standards, donor requirements, and satisfy local stakeholders. In UNDP, Project Quality Standards provide the quality standards for programming.

Risk Management in International Development

Development organisations are confronted with a wide variety of risks when implementing development projects, particularly in fragile and conflict affected states. International development projects often face implementation challenges related to:

- Lack of quantifiable market rewards and profitability incentives that characterise other industries’ projects,

- Complex and often intangible nature of projects to be delivered under complex social, economic, and political factors that affect the quality of goods/services,

- External driving forces such as international politics, currency exchange or global supply chains,

- Embargoes and sanctions regimes from the UN, EU, US and other donor countries on specific countries, individuals, groups, or organizations affect the ability to engage with debarred/sanctioned entities and individuals, or access goods, services, or cash arrangements in sanctioned countries,

- Political and legal system of the country, often with poor infrastructure and banking systems,

- High security risks, potential social unrests, active conflicts, or post-disaster/post-conflict/post-war situations, and operating in some of the most remote and challenging locations in the world,

- No/limited time between financing approval and beginning of the project life cycle,

- Resource limitation and a high degree of public accountability and reporting,

- Complex stakeholder management and ambiguous role of donor and project supervisors,

- Ineffectiveness of one-size-fits-all approaches.

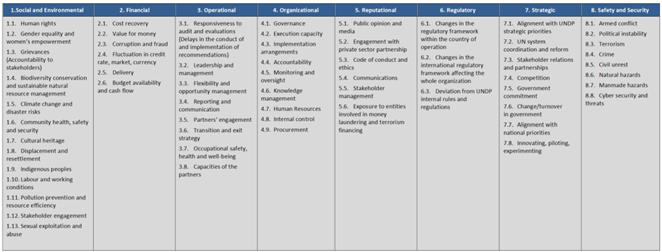

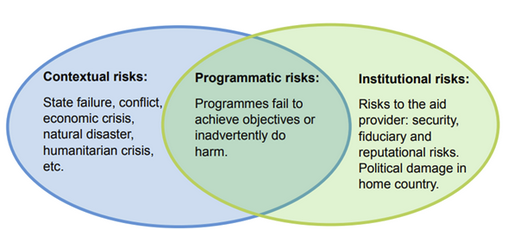

These require a standardised and flexible approach to project management, supported by sound and continuous risk management. From the perspective of international aid, OECD DAC created an internationally recognized method to categorise risks into three overlapping circles, referred as the ‘Copenhagen Circles’ (Figure 1):

- Contextual risks: a range of potential uncertainties that may arise from a particular context and facilitate or hinder progress towards development priorities of a given society. These may include the risk of political destabilisation, violent conflict, economic deterioration, natural disaster, humanitarian crisis, cross-border tensions, etc. Development agencies and external actors have only a limited influence on whether a contextual risk event can occur but can react to minimise the effects on the objectives.

- Programmatic risks: the risk that programmatic interventions do not achieve their objectives or cause inadvertent harm by, for example, exacerbating social tensions, undermining state capacity, and damaging the environment. Programmatic risks may relate for instance to weaknesses in project design and implementation, failures in coordination, and dysfunctional relationships between development agencies and their implementing partners.

- Institutional risks: a range of potential uncertainties that could facilitate or hinder the efficiency and effectiveness of core operations within the organisation and its staff. These may include management failures and fiduciary losses, exposure of staff to security risks, and reputational and political damages. Current risk management practices are predominantly focused on institutional risk reduction.

In international development projects, risk management is not just about risk reduction, it involves balancing risk and opportunity, or one set of risks against another. Development organisations have adopted different tools for the management and monitoring of risks. Some focus on risk management at the project level, while others at the portfolio and programme level, and these include different risk categorization. These categorizations are captured in each organisation’s Enterprise Risk Management policy, Risk Appetite, and individual policies and procedures. The following sections will focus on risk management frameworks within the Global Fund and UNDP.

Risk Management in the Global Fund

Global Fund Risk Management Framework

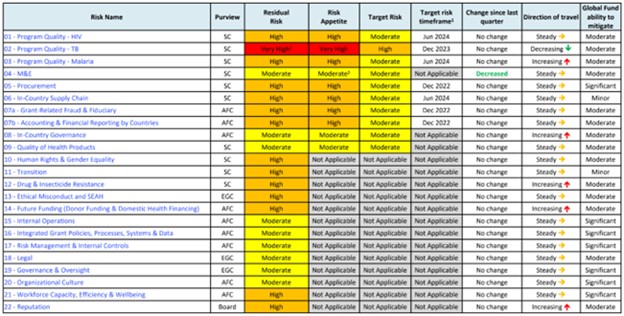

The overall risk management architecture of the Global Fund is informed by the Global Fund Risk Management Policy (2014), the Risk Appetite Framework (2018 and 2023 amendment), the Enterprise Risk Management Framework (2023 update - see annex 1 of the Risk Management Report to the 49th Board Meeting), and the Risk Management Operational Policy Note (2024).

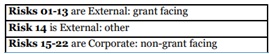

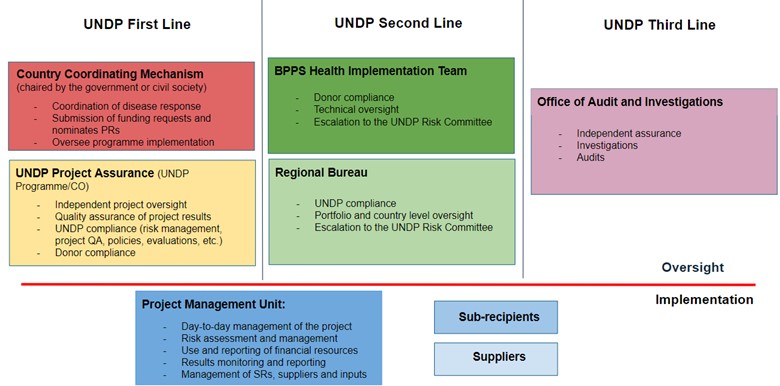

Following international standards, the Global Fund employs a ‘three-lines of defence’ model to risk management. Each line is responsible for specific core risk management activities The Global Fund Secretariat holds first line (risk owner) and second line (oversight) of defence functions, while the Office of the Inspector General and external auditors hold third line of defence (independent assurance) functions.

Implementers (i.e. Principal Recipients (PRs), in-country partners, and Country Coordinating Mechanisms (CCMs) are ‘front line defence’ and are responsible for managing the risks to achieving grant objectives on a day-to-day basis. The risk management activities of the front line of defence are outside the scope of the Global Fund risk management policies. The PRs’ internal risk management processes are regulated by the organisations’ own risk management policies and procedures. The three lines of defence oversee front line implementation and management of risks.

From the Global Fund, implementation of the grants is overseen by the three lines of defence. More specifically:

- The Global Fund Secretariat Country Teams, with support from the Local Fund Agents (LFA), are responsible for day-to-day implementation oversight, on behalf of the Global Fund;

- The Global Fund Secretariat Risk Department and other oversight functions (Business Risk Owners) together with Global Fund Senior Management define the risk management framework and provide oversight, guidance, and support to Country Teams; and

- The Office of the Inspector General and external auditors, provide independent assurance regarding the management of risks and controls by the Country Team and Business Risk Owners and efficient use of Global Fund resources.

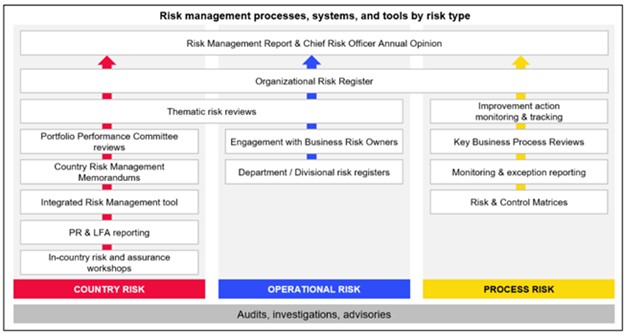

The Global Fund categorises risk sources into 3 broad thematic areas: 1. country risks, 2. operational risks and 3. process risks. The Global Fund Secretariat is concerned with the management of operational and process risks. PRs and country portfolios are concerned with the management of country risks, which include:

Local Fund Agent

The Local Fund Agent (LFA) is an entity contracted by the Global Fund for a particular country to undertake an objective examination and provide independent professional advice and information relating to grants and Principal Recipients (PRs). Within the Global Fund’s risk management framework, the LFA provides an independent in-country verification and oversight mechanism in addition to Principal Recipient’s assurance. The Global Fund expects LFAs to proactively identify and alert it to any issues that may prevent activities and funding from reaching the intended beneficiaries in the quantity, time, and quality intended, and the Global Fund programmes from reaching their objectives. Based on the Global Fund Country Team’s risk assessment of the particular portfolio, the LFA’s scope of work is tailored to the specific circumstances of the grant.

Although in some cases the LFA is UNOPS, this is usually a private consulting firm, competitively selected (see list of LFAs ). As a third-party and following the ‘single audit’ principle governing UNDP, the LFA does not have access to UNDP Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) (Quantum), contracts, selection processes, and other critical information. Therefore, the LFA does not replace standard UNDP internal control systems and is not mandated to assess compliance with UNDP policies. As stated in the UNDP-GF Framework Agreement (Dec 2024), UNDP as PR will implement or oversee the implementation of the Program in accordance with UNDP regulations, rules, policies and procedures, thus standard risk management mechanisms apply, in addition to GF specific oversight requirements.

Practice

Pointer

Practice

Pointer

Challenging Operating Environment (COE) Policy

The Global Fund has a country-classification mechanism to ensure that operational policies and processes reflect contextual needs for countries. These categories are updated every allocation period based on the allocation amount, the disease burden, and strategic impact of the country. Countries are classified as:

- Focused Portfolios are generally smaller portfolios, with a lower disease burden, and a lower mission risk.

- Core Portfolios are generally larger portfolios, with a higher disease burden, and a higher mission risk.

- High Impact Portfolios are generally very large portfolios with mission critical disease burdens.

See the introduction of the GF’s Operational Policy Manual (2024) for the portfolio categorization.

The Global Fund also use two cross-cutting classifications to further differentiate portfolios:

- Challenging Operating Environments (COEs) are countries or regions with complex natural or manmade crises and instability with an impact on the risk of death, disease, and breakdown of livelihoods.

- Transitioning components are those that are approaching transition from receiving funding from the Global Fund.

To be able to operate in contexts of various degrees of complexity, in addition to the Risk Management Policy, the Global Fund has developed some specific risk management tools.

The Global Fund recognizes the need to apply a tailored approach for COEs focusing on providing a set of flexibilities when implementing Global Fund grants and this is articulated in the COE Policy (2017).

Challenging Operating Environments are countries or regions characterised by weak governance, poor access to health services, and man-made or natural crises. The policy classifies COEs based on countries with the highest External Risk Index (ERI) level in the Global Fund portfolio and allows for ad hoc classification to enable rapid responses to emergency situations. Once a country (or part of it) is categorised as a COE, the Global Fund can tailor the flexibilities that would apply. The flexibilities may relate to the following:

- Access to funding: The Global Fund can allow the extension of existing grants, non-Country Coordinating Mechanism (CCM) applications, and extended allocation where a COE country is no longer eligible for funding.

- Implementing entities: While the CCM nomination of the Principal Recipient (PR) is preferred, in COE countries the Global Fund may assume the responsibility for selecting the PR.

- Grant implementation: Where relevant and possible, goals, targets, activities, and budgets can be adjusted, and implementation arrangements changed to reach target populations.

- Procurement and supply chain: Where existing in-country supply chain systems are dysfunctional, disrupted or at risk of disruption, third-party providers may be selected for part or all the supply chain management functions. In emergency situations, PRs with strong procurement and supply chain capacity may be selected.

- Monitoring and evaluation: The Global Fund recognizes the risks associated with data collection and data quality in COEs due to weak health data systems. It addresses these risks by insisting on strengthening of Health Management Information Systems (HMIS) and using different types of data (surveys, evaluations, quantitative and qualitative sources)

- Financial management: The flexibilities on key financial processes include, among others: ease of reprogramming process with a high-level budget based on past grant assumptions, reliance on implementers’ own assurance mechanism where deemed strong, outsourcing of accounting and/or fiduciary function, and extension of audit and reporting due dates.

The Challenging Operating Environment Operational Policy Note regulates the implementation of the COE policy. The level of verification and scope of the Local Fund Agent’s assurance services may be tailored in line with the nature of the crisis and associated risks. This tailoring is conducted by the Global Fund’s Country Teams.

UNDP is often nominated as PR in COE countries. As UNDP-implemented Global Fund projects adhere to UNDP’s regulations, rules, policies, and procedures. Most flexibilities would be negotiated during grant-making and the Country Office is advised to request support of the UNDP Global Fund Partnership and Health Systems Team and the Regional Bureau, as early as possible, during the funding submission and the grant making process.

Additional Safeguard policy (ASP)

The Additional Safeguards Policy (ASP) (2004) is a set of measures that the Global Fund introduces whenever “the existing systems to ensure accountable use of Global Fund financing suggest that Global Fund monies could be placed in jeopardy without the use of additional measures”. Examples of criteria for invoking ASP include significant concerns about governance; the lack of a transparent process for identifying a broad range of implementing partners; major concerns about corruption; a widespread lack of public accountability; recent or ongoing conflict in the country or region of operation; political instability or lack of a functioning government; poorly developed or lack of civil society participation; financial risks such as hyperinflation or devaluation; or lack of a proven track record in managing donor funds. The decision to invoke the ASP Policy, available in the Global Fund’s Operational Policy Manual (2024), is often triggered by capacity concerns on the Principal Recipient (PR) or the Sub-recipients (SRs), lack of transparency in the selection of grant implementers, political instability, conflicts, lack of participation, etc.

ASP measures include:

- Selection of the PRs by the Global Fund

- Selection of the SRs by the Global Fund

- Specific risk mitigation measures, such as:

- Installation of fiscal/fiduciary agents

- Restricted cash policy, or no-cash to SRs

- Use of GF Pooled Procurement Mechanism

UNDP is often nominated as PR in ASP countries. As UNDP-implemented Global Fund projects adhere to UNDP’s regulations, rules, policies, and procedures. Most flexibilities would be negotiated during grant-making and the Country Office is advised to request support of the UNDP Global Fund Partnership and Health Systems Team and the Regional Bureau, as early as possible, during the funding submission and the grant making process.

Global Fund Risk Management Requirements for PRs

Once UNDP is confirmed as interim Principal Recipient (PR), the capacity of the local UNDP office is assessed during the grant negotiation phase, through a UNDP tailored Global Fund Capacity Assessment Tool (2023). Therefore, the grant is ultimately approved on the basis of a positive assessment of local UNDP Office capacities to implement the grant and effectively manage risks.

The UNDP-GF Framework Agreement (Dec 2024) Article 2, Annex A, states that:

“The Principal Recipient will implement or oversee the implementation of the Program in accordance with UNDP regulations, rules, policies and procedures and decisions of the UNDP Governing Bodies, as well as the terms and conditions of the relevant Grant Agreement. The Principal Recipient will be responsible and accountable to the Global Fund for all resources it receives under the relevant Grant Agreement and for the results that are to be accomplished.”

It is therefore expected that standard UNDP’s internal controls systems, policies, and regulations, as set out in UNDP’s Programme and Project Management (POPP), are used to provide the appropriate level of assurance throughout the design and the implementation of the Global Fund grant.

The UNDP-GF Framework Agreement (Dec 2024) , includes new provisions for the prevention and management of Sexual Exploitation, abuse and harassment (SEAH). These further define UNDP’s standard SEAH provisions and clarify the standards that apply to SEAH prevention and management when implementing Global Fund resources. Details are provided in the UNDP risk management measures during grant formulation and UNDP risk management measures during grant implementation sections of this Manual.

To support Country Offices, UNDP has developed a number of stand-alone risk management tools for a risk-informed implementation of Global-Fund-funded projects. These are listed in the Risk management architecture for UNDP-implemented Global Fund projects section of this Manual and are in addition to standard UNDP risk management procedures, as listed in POPP and mapped here.

When selected as PR, UNDP is entrusted with Global Fund resources, and it is therefore fully accountable in ensuring that (i) the funds are efficiently and effectively directed to achieving programmatic results and reaching people in need and (ii) programmatic and financial data are accurate, timely and complete. UNDP accountability also extends to the management of risks related to the activities implemented by the Sub-Recipients (and their Sub-Sub-Recipients) contracted by UNDP.

Therefore, where Sub-Recipients are involved, the Principal Recipient has the responsibility to manage the Sub-Recipients. In managing the SRs, UNDP is also responsible for managing the Sub-Sub-Recipients (SSRs) and risks that can emerge from the engagement between SRs and SSRs. For more details on SR selection, capacity assessment requirements and process, refer to the Sub-Recipient Management section of this Manual.

Global Fund Risk Management Requirements During Funding Request

The Funding Request is submitted by the Country Coordinating Mechanism (CCM) for technical review by the Technical Review Panel. Often the Principal Recipients (PRs) are not confirmed at this stage of the request. However, in case the CCM has already confirmed that UNDP will be/continue to be the PR, the Country Office is invited to contribute to the submission and risk identification process. Although most of the risk assessments are conducted during grant-making, the funding request is expected to include a number of risk management considerations. These include:

- Eligibility requirements for CCMs (required by the CCM).

- Country dialogue requirements by the CCM for an inclusive and transparent funding application development process (required by the CCM).

- Co-financing, sustainability and transition planning requirements with considerations on how to strengthen them - see Global Fund Guidance Note on Sustainability, Transition and Co-financing (2022) (required).

- Protection from sexual exploitation, abuse, and harassment (SEAH) is a priority for the Global Fund and all funding submissions are encouraged to include the Global Fund Risk Assessment Tool for Sexual Exploitation, Abuse and Harassment (SEAH) and corresponding mitigation measures (recommended).

- Analysis of human-right and gender-related barriers in access to services and promote gender equality and health equity. An analysis of the social and structural drivers behind barriers related to human rights, gender equality and health equity (recommended).

- A preliminary assessment (required) of up to 3 key risks and mitigation measures along 3 key risk areas:

- Procurement and management of health products, including those associated with clinical laboratories.

- Flow of data from service delivery points.

- Financial or fiduciary matters.

- A draft mapping of the implementation arrangements for the proposed grant (recommended).

- Plans and capacities to prepare and respond to pandemics (required).

- A reflection from previous lessons, risks and capacity issues identified in previous implementation periods and integration of these in the new request (required).

In parallel, the Global Fund’s Country Teams conduct their risk assessments of the funding request. These can include:

Global Fund Review of Risk Management During Grant Implementation

The implementation of the grant is reviewed by the Global Fund, through their three line of defence model. This is done by monitoring Principal Recipient’s (PRs) risks and performance through:

- PR risk reporting -

- conducted through the Progress Update and/or Disbursement Request (PU/DR) - see the Grant reporting section of this Manual for details and the PU/DR instructions (2023). In addition to an update on the risks affecting the portfolio and the status of the Key Management Actions (KMAs), the PU/DRs also include a review of risk of stock-out and expiry. The Global Fund must be notified of imminent expiry and stock-out risks. See Health Product Management section of this Manual.

- Pulse Checks are submitted twice per implementation year for High Impact and Core portfolios. The Pulse Check is submitted in Q1 and Q3, between mid-year Progress Updates (PU) and year end Progress Updates and Disbursement Requests (PUDR). See Global Fund Pulse Check guide (2024).

- Audits - see audit and investigation section of this Manual.

- Local Fund Agent (LFA) verification - PRs work with the LFA and provide information related to the management of the grants to comply with the grant assurance activities. See the LFA section of this Manual.

- Engagement with Country Teams - participate in regular virtual or in-person communications with the Country Teams to discuss progress, risks, and issues.

The Global Fund assesses and communicates grant performance and risk management decisions through grant performance letter, PR performance qualitative assessment and performance letter. The latter is a communication from the Global Fund highlighting grant and PR performance with specific areas for action. It includes, at a minimum, the list of prioritised risks, mitigating actions and timelines relevant to the PR. The Global Fund can also leverage in-country programme review and evaluation to validate country portfolio risks and identify issues where additional support, flexibilities and/or innovation are needed.

Risk management in UNDP

Navigating through the complexity of multiple uncertainties is at the core of UNDP’s quest for innovative solutions to development and organisational challenges. UNDP’s Enterprise Risk Management policy (ERM) provides an overarching framework to ensure foresight and risk-informed decisions across all levels of the organisations, including all projects, to maximise gains and avoid unnecessary losses.

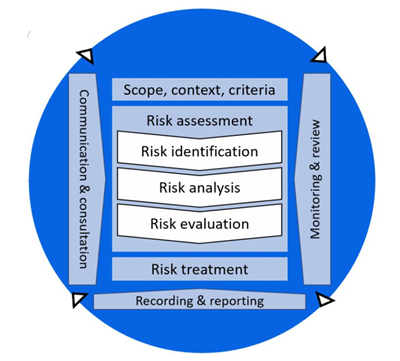

UNDP’s approach to risk management is based on the 2018 edition of the international standards for risk management, ISO 31000:2018 “Risk management – Principles and guidelines”. UNDP defines risk as the effect of uncertainty on organizational objectives, which could be either positive and/or negative.

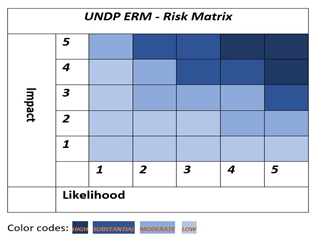

In line with the ISO 31000:2018, the UNDP’s ERM methodology consists of 6 key elements, as per Figure 4 below. Each step is further detailed in the following sections of this guidance.

Under the UNDP’s ERM umbrella, risk management is integrated through prescriptive UNDP’s policies and procedures which are designed to manage selected categories of risks. A visual guide of the UNDP ERM policy is available here and mapping of some key UNDP risk management tools and policies to guide risk assessment, treatment and monitoring along the UNDP’s risk categories is available here.

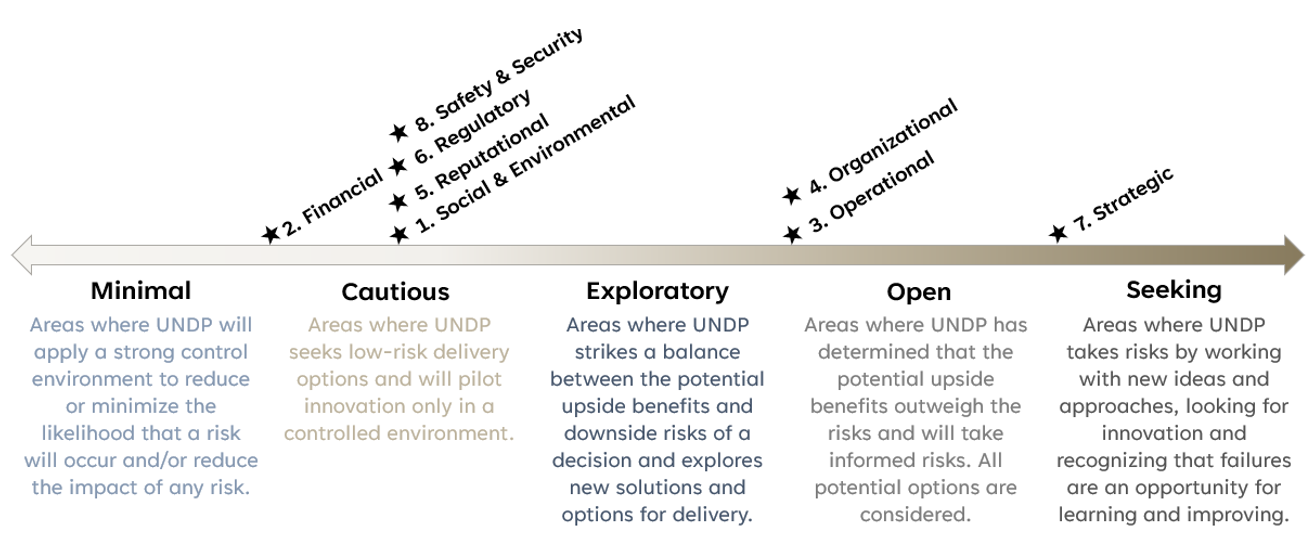

The UNDP’s Risk Appetite Statement (RAS) and the UNDP’s Risk Appetite Statement Guidance set UNDP’s internal preference regarding the level of risk to take in a given situation. The purpose of the RAS is to ensure consistent and effective understanding of the amount and type of risk UNDP is willing to accept to deliver on its strategic objectives. UNDP’s risk appetite across risk categories is summarised in Figure 5 below and these are expected to be consulted during the risk identification process and to guide the design of risk treatment actions.

Risk Management in UNDP-managed Global Fund projects

Risk management architecture for UNDP-implemented Global Fund projects

The Global Fund supports countries in pursuing ambitious targets, resulting in a direct impact on HIV, TB, and malaria epidemics, which often include the provision of lifesaving services. Global Fund-funded projects follow very stringent donor requirements, as highlighted in this Manual. In addition, high volume, health implementation projects are high-risk for a number of very specific factors:

- Health products. Global Fund-funded projects are highly commoditized, where UNDP, as Principal Recipient, leads in the selection, quantification, procurement, storage, distribution, and quality assurance of health products. Delays in supply chains, disruption in diagnostics and treatment services, or poor quality of health products can have life threatening consequences. In addition, given the high value and marketability of these health products, risks of fraud, waste, or theft are significant.

- Complex operating environments. UNDP is nominated as Principal Recipient in countries with complex operating environments, these are often countries facing conflict, emergencies, sanctions, weak governance, or significant capacity constraints.

- Use of national systems. Due to its mandate and in line with donor’s requirements, UNDP implements these projects through existing national systems, to strengthen institutional capacities, infrastructure, health systems and processes.

To manage the risks emerging from the above systemic challenges, UNDP has established a comprehensive risk management framework to mitigate and manage the high risks associated with the implementation of the Global Fund portfolio. This framework includes:

- The Global Fund portfolio is integrated with UNDP’s umbrella Enterprise Risk Management Framework and fully aligns its implementation to UNDP’s policies, rules and regulations.

- Where nominated as Principal Recipient, UNDP utilises the Direct Implementation Modality for Global Fund grants, whereby dedicated Project Management Units (PMUs) are established within each UNDP Country Office (CO) to directly oversee and manage grant implementation.

- There is global oversight and monitoring of UNDP’s Global Fund portfolio by the Global Fund Partnership and Health Systems Team (GFPHST), in UNDP BPPS in coordination with Regional and Central Bureaus.

UNDP risk management measures during grant formulation

A number of standard and key controls should be established in the key phases of project formulation and implementation to ensure a mitigation of some of the most common risks faced by UNDP-implemented Global Fund projects, as listed in the Risk Catalogue for Global Fund projects. Some key risk management considerations to embed in the formulation of the grant are listed below.

Risk Assessment during key start-up activities: when notified that UNDP is being considered as Principal Recipient (PR), the UNDP Country Office with support from the Regional Bureau and the BPPS GFPHST, should conduct an assessment of the risks in taking the PR role to inform the decision to accept the role and the formulation of the transition and grant making work plan. See Principal Recipient Start-up section of this Manual.

Project quality assurance and appraisal - UNDP POPP (Programme and Project Management (PPM) Appraise and Approve) requires the appraisal of the quality of every project before finalisation. This is done via a Project Quality Assurance assessment of the project by the Project Assurance function in the Country Office (CO) and a Local Project Appraisal meeting. In this regard, during the formulation of Global Fund-funded projects, ensure:

- The CO programme team (as Project Assurance) is involved in the quality review of the project during the grant formulation phase. If UNDP is not assigned as PR during the funding request, consider involving the CO programme team as soon as possible during the negotiation of the project.

- UNDP’s Quality Standards for Programming are reflected in the formulation of the funding request, the negotiation of the grant (if UNDP is not assigned as PR during the funding request stage) and the UNDP project document.

- It is recommended to ensure a UNDP’s preliminary feedback to the draft funding request is collected and integrated in the funding request / project as soon as possible. This feedback includes programming quality, security, health procurement and supply management, oversight, financial management, human resources, and monitoring and evaluation considerations from the UNDP CO, BPPS Global Fund Partnership and Health Systems Team (GFPHST). If the project has been classified as a ‘high-risk project’ by the Regional Bureau/BPPS, also include Regional Bureau’s feedback.

Construction – The UNDP Construction Works policy and the PPM Appraise and Approve policy foresee the delegation for construction works by the Regional Bureau to the Resident Representative (RR) before project approval. Ensure this is obtained before the finalisation of the project.

UNDP risk management measures during grant implementation

Sub-Recipient management: Ensure ongoing management of Sub-Recipients (SRs) as per Sub-Recipient Management section of this Manual, and specifically:

- Make sure Capacity Development (CD) plans are in place, addressing key weaknesses identified in the SR Capacity Assessment (CA). To be meaningful, the implementation of the capacity development plan should be completed before the end of the grant, and regularly monitored.

- Ensure financial verification, availability of supporting documents, and alignment with the agreed work plan as precondition for the approval of payments/cash advances.

- Conduct periodic risk-based on-site verifications covering different implementation aspects in the same visit (programme, M&E, health products management, asset management), follow up on the findings/issues/risks raised, and to the extent possible, involve end-users in the monitoring of project results.

- Review procurement conducted by SRs to ensure a competitive process.

- Issue the periodic SR management letters on time and ensure that detailed and customised recommendations are raised to address programmatic and financial challenges.

- Escalate any SR reporting challenges to the Project Board and the relevant government ministry.

Financial management: Ensure financial management as per Financial Management section of this Manual, and specifically:

UNDP Risk Management Process

Scope and Context

The UNDP Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) framework defines the scope and criteria of UNDP’s risk management across the organisation and its projects.

The first step of a risk management process is gathering an understanding of the internal and external context under which the project will operate and seek to achieve its objectives. Contextual factors affecting a project are external and internal. It is important that these are identified and captured in the grant and project document, and are revisited regularly, throughout the risk management process, particularly during annual planning and risk reviews.

Examples of external factors particularly relevant to Global Fund-funded projects:

- Security and conflict landscape of the country, presence of violence, conflicts, socio-political tensions, crime, humanitarian crisis, displacements, etc.

- Political stability, national priorities, capacity of government to provide services

- Economic, social, cultural, ethnic, embargoes and sanctions regimes and financial factors and drivers of inequality, stigma, conflicts, corruption, and poverty

- Country’s legal and human rights framework, regulatory environment

- Market, infrastructures, inflation, sanctions, etc.

- External stakeholders and relationships, their capacities, presence, technical expertise, perceptions, values, expectations, risk tolerance

- Natural hazards, geography, climate, environmental frameworks

Examples of internal factors particularly relevant to Global Fund-funded projects:

- UNDP’s mandate in country, United Nations Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework and Country Programme Document

- Existing Country Office’s (CO) capacities, resources, knowledge, culture, systems, processes

- Governance mechanisms, institutional arrangements, organisational structure, roles, and accountabilities

- Standards, policies, guidelines, internal controls, wider risk management and control environment of UNDP

- Data, information systems, information flows

- Relationship with internal stakeholders

- Interdependencies and interconnections across projects

Practice Pointer

Practice Pointer

In addition, a list of key risks affecting the UNDP-implemented Global Fund project can be accessed here.

Contextual factors and risks are captured in the funding request and the UNDP project document, inform the risk assessment process, and are revisited regularly, throughout the risk management process.

Risk assessment

As per UNDP’s Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) framework and ISO 31000:2018, risk assessment consists of three steps:

- Risk identification,

- Risk analysis, and

- Risk evaluation

Risk assessment is an ongoing and iterative process, completed no less than once a year, through risk reviews. The risk review process is described in the Risk monitoring and review section of this Manual.

Risk identification: this is the process to identify and describe risks and opportunities that can affect the achievement of objectives (either positively or negatively). UNDP has a number of predefined and prescriptive tools that can inform the various stages of the risk management process. These are available here. However, given each context is unique, it is a good practice to ensure that risk identification leverages a variety of data, sources of information, and methods.

Common risk identification approaches include:

- Review of the context, scope planning, preliminary schedule planning, and resource plan. This is a critical step in any project management process, and includes a mapping of all the unknowns, strengths, and weaknesses, identified in the work breakdown structure, critical path, detailed project costing, market analysis, estimates, dependencies, etc. This is a multi-functional process and requires technical inputs from the broader Country Office, and regional/global teams.

- Brainstorming, Delphi technique with multi-dimensional teams. This goes beyond discussions with project/programme team. It includes a brainstorming of what could go wrong with technical teams, such as procurement, security, human resources, finance, as well as gender specialist, health, human rights and peace and development advisors, etc. both in country and regional/global offices, inside or outside UNDP.

- Retrospective analysis of earlier projects, past performance, evaluations, reviews, lessons learned. This includes a review of past Global Fund or health implementation projects, both in country and globally. Data can be extracted from risk register/dashboard, evaluations, reviews, lessons learned, audits, interviews, progress reports, etc.

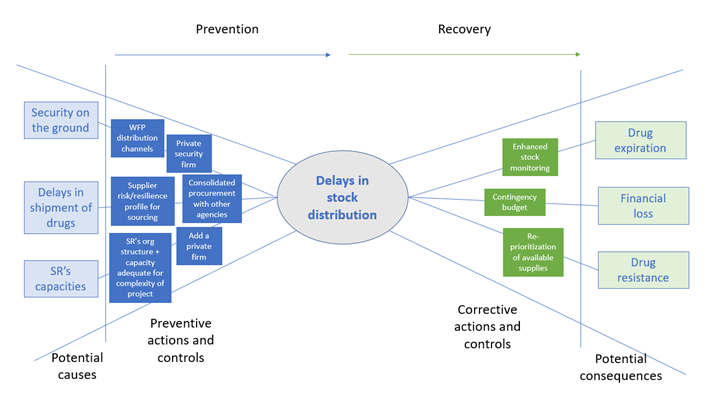

Common risks identified in Global Fund projects

Global Fund projects are implemented in rapidly changing and complex operating environments. Despite their differences, there are ranges of contextual, operational and institutional risks that impact the risk profile of Global Fund-funded projects. The Risk Catalogue for Global Fund projects is a compilation of common risks faced by Global Fund-funded projects as reported by Project Management Units (PMUs), Country Offices, Regional Bureaus, audits, evaluations, and oversight. These risks are organised along the 8 UNDP ERM risk categories and can be used as a practical input to support the risk identification process during project design, planning, and risk reviews. For each possible risk, a list of potential contributing factors/causes is provided to help with risk identification and analysis. It is recommended to ensure risk statements are as specific as possible, as per guidance in the Risk Reporting and Recording section of this Manual, and some suggestions are provided on this in the risk catalogue. The risk catalogue expands on the following common risks identified in Global Fund projects:

- Human rights barriers and/or gender stigma

- Ineffective stakeholder engagement

- Sexual exploitation and abuse, and sexual harassment

- Community health, safety, and security incidents

- Unsafe working and labour conditions

- Pollution and healthcare waste

- Inadequate Monitoring & Evaluation (M&E) and poor data quality

- Substandard quality of health products

- Drug stock outs and overstocks

- Poor warehouse management and inventory management system

- Delays in in-country distributions

- Delays in procurement/contracting

- Ineffective Country Coordinating Mechanism (CCM)/board oversight

- Gaps in PMU’s human resources

Financial

- Ineligible expenditure

- Theft, diversion, or fraud of financial and non-financial assets

- Loss or damage to non-financial assets

- Low/delays in delivery

- Inadequate Sub Recipient (SR) internal controls, reporting, and compliance capacities

- Poor oversight of SR financial and programmatic performance

- Poor engagement in and effectiveness of TB interventions

- Poor engagement in and effectiveness of HIV interventions

- Poor engagement in and effectiveness of Malaria interventions

- Poor sustainability

- Inability to provide co-financing

- Delays in submission of quality results reports

- Public and donor opinion

- Changes in in-country regulatory framework

- Failure to observe UNDP policies and procedures

- Delays in government decisions

- Changes in government

- Safety risks for staff, Sub-recipients, or target groups

Risk Treatment

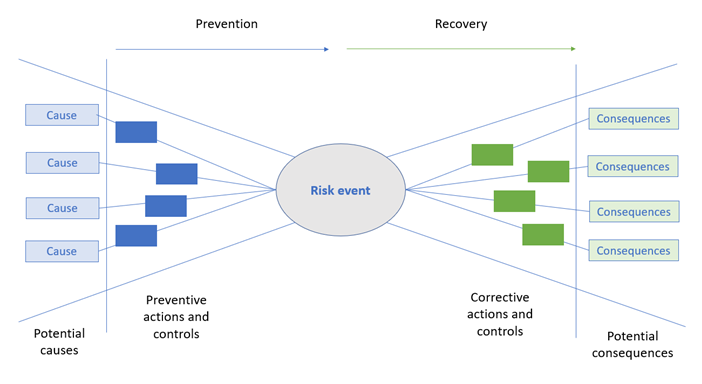

A risk treatment is any action taken to prevent or respond to a risk or an opportunity. Following the risk assessment, a key step of the risk management process is the identification of specific treatment actions.

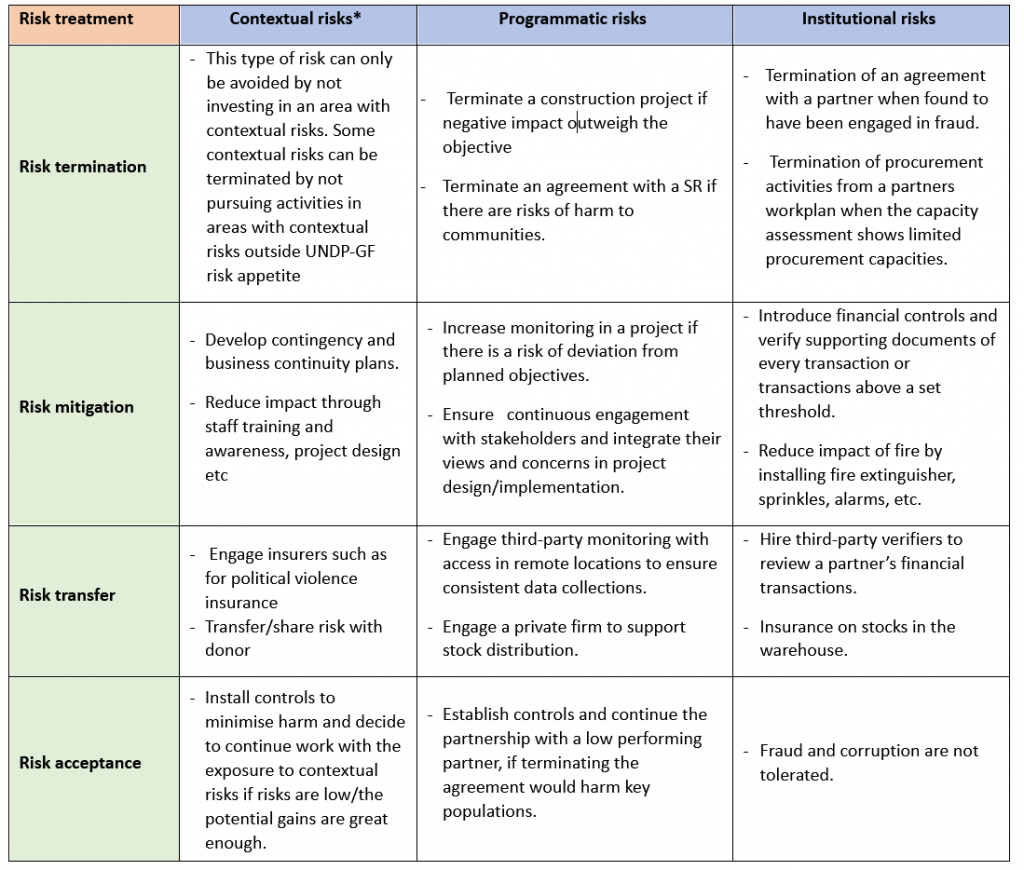

UNDP’s Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) policy has identified 4 types of response:

- Terminate - eliminate the activity that triggers such a risk

- Transfer - passing ownership and/or liability to a third party

- Mitigate - reducing the likelihood and/or impact of the risk below the threshold of acceptability

- Tolerate - accepting the risk level, usually for low (impact/likelihood) risks

Practical examples of treatment actions along the 3 risk categories are provided below.

The ability of development actors to influence contextual risks (inflation, change in government leadership, natural disasters, conflicts, etc.) is often very limited. This means that the ability to treat contextual risks is often limited to developing contingency plans or accepting the risks, if low-risk and/or within UNDP’s risk appetite.

For each risk, UNDP assigns a Risk Owner and a Risk Treatment owner.

- Risk Owner – the person with the ultimate accountability and authority to manage the risk. At the project level, this is often the project manager.

- Risk Treatment Owner – the person assigned with the responsibility to ensure that a specific risk treatment is implemented.

Risk recording and reporting

UNDP’s Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) policy requires that the risk management process and its outcomes are documented and reported in order to facilitate communication, inform decision making, improve risk management processes, and assist coordination with stakeholders. In UNDP, the Risk Register is the method to record and report on the risk management process and to assign the accountability for the treatment of the risks. An offline Portfolio/Project Risk Register Template is available in the Programme and Project Management (POPP), which is mirrored in the UNDP Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) system (Quantum). Specifically, the following information are populated under the Project Risks section of the Quantum Project Results module:

| Risk Statement | Risk Treatment | Risk Escalation Status |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

The risk register captures the results of the previous two steps: the risk assessment and risk treatment. The risk register describes the risk statement, the risk analysis, the chosen risk treatment, risk owner, and treatment owner.

Practice Pointer

Practice Pointer

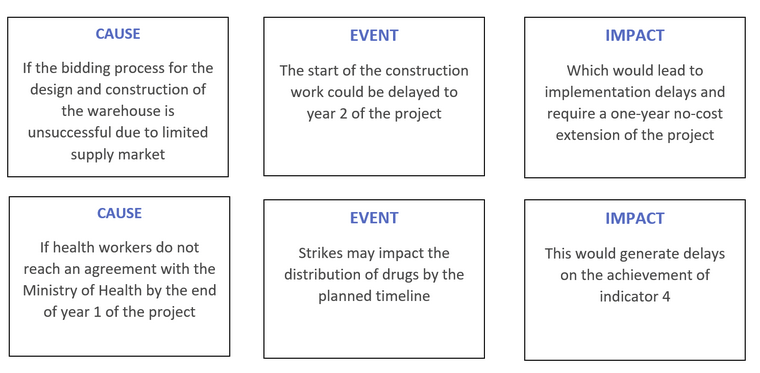

The Risk Statement is a sentence, clearly representing the risk assessment process. The risk statement should be framed as conditional events and should show a causal relation between the cause, the event, and the impact.t is structured as follows:

Risk escalation process

All UNDP personnel have a role in risk management and are responsible for identifying and managing the risks that affect the achievement of objectives related to their areas of work within their delegated authority. All UNDP personnel are also responsible for reporting allegations of misconduct as per process detailed in Where to Go When Guide of the UNDP Ethics Office. All UNDP personnel must inform themselves of their responsibilities and obligations as outlines in the UNDP Code of Ethics and consequences outlines in the UNDP Legal Framework for Addressing Non-Compliance with UN Standard of Conduct.

When a Risk Owner and/or a Project Manager of a UNDP-implemented Global Fund project faces circumstances pertaining to the risk treatment that exceed his/her authority/mandate or expertise, the risk is escalated. Global Fund project level risks are escalated upward according to the UNDP Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) risk escalation conditions:

- Risk treatment requires expenditures that are beyond what the Risk Owner is authorised to decide; and/or

- Risk cuts across, or may impact, multiple offices (e.g. reputational risk, changes to corporate policies); and/or

- Grievances from stakeholders have been received to which the Risk Owner cannot impartially and/or effectively respond (e.g. through UNDP’s Stakeholder Response Mechanism); and/or

- A serious security incident has occurred which has impacted UNDP personnel, facilities or programmes or the security environment has deteriorated requiring additional treatment measures and/or security advice; and/or

- When the risk significance level is determined to be High.

Risks are escalated from the Project Manager / Risk Owner through the project risk register in Quantum by changing the ownership of the risk and only after the receiving manager has confirmed that s/he accepts the ownership. See UNDP ERM policy for details.

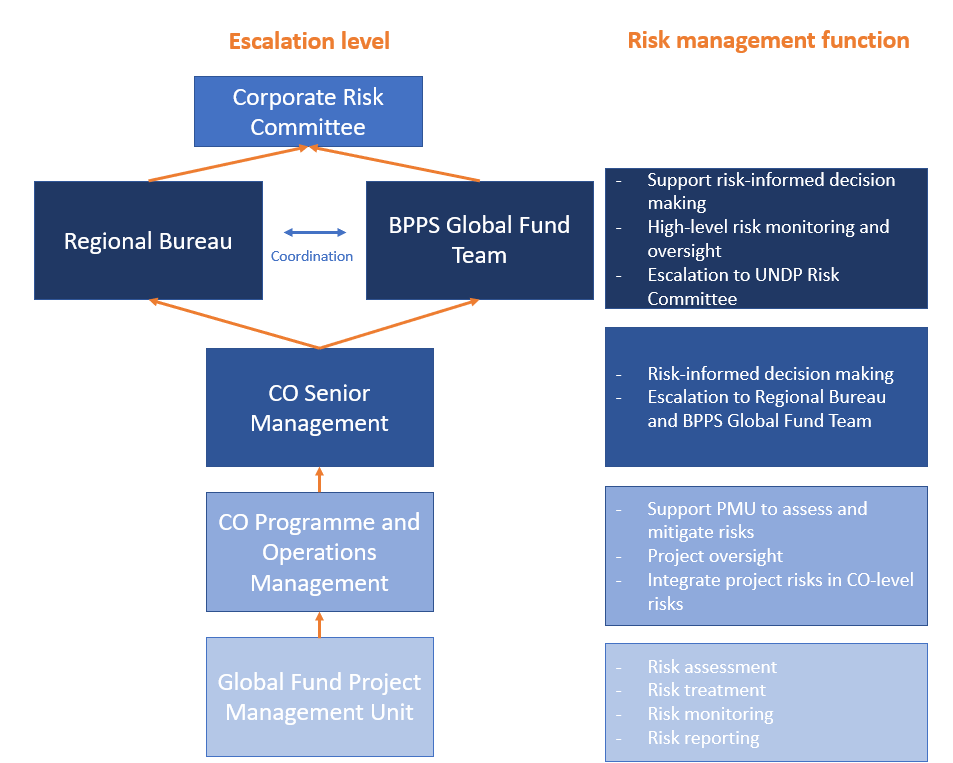

Risk management is a bottom-up process and for risks identified by the project, the risk escalation flow in Figure 8 is followed:

Figure 8. Risk Escalation Flow for GF Projects: adapted for GF project from UNDP ERM Risk Escalation Guideline

In addition, the BPPS Global Fund Partnership and Health Systems Team (GFPHST) developed additional escalation criteria with a flow from the GFPHST to the RRs and the Regional Bureaus through the semi-annual reporting of the risks identified by BPPS. These are triggered when the GFPHST during the quarterly and semi-annual Performance and Risk Reviews, or as per the Team’s regular risk monitoring and oversight functions, recognizes that issues have materialized and require Regional Bureau’s involvement.

Communication and consultation

Risk management is consultative, and communication is ensured throughout the risk management process. This includes:

- Ensuring, effective and informed engagement and participation of the stakeholders and at-risk groups involved in the project

- Ensuring an inclusive risk management process, by bringing together all required technical expertise in the risk management cycle

- Provide sufficient information to ensure oversight and risk-informed decision making through dedicated discussions on risks during meetings with the Country Coordinating Mechanism (CCM) and between the BPPS Global Fund Partnership and Health Systems Team (GFPHST) and the Regional Bureau.

In Global Fund projects, the Local Fund Agent is expected to escalate risks to the donor. However, risk communication can and should also start from UNDP Project Management Unit (PMU). This can take place internally across the UNDP three lines of defence, as per UNDP-Global Fund risk management framework, and/or from the Principal Recipient to the CCM and through letters to the donor, for critical (and often contextual or programmatic) risks.

Risk monitoring and review

Risk monitoring is an integral part of the project Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E) process which is expected to assure that the project risk management process is effective and contributes to achieving project objectives.

Who does it? Within UNDP, risk monitoring is conducted at several levels, as per the three lines of defence and the framework listed in the Risk management architecture for UNDP-implemented Global Fund projects section of the Manual.

The risk owner is responsible for monitoring progress and effectiveness of the risk treatment action and ensuring that regular risk reviews take place.

How is it done? Risk monitoring is closely linked with project compliance and M&E activities. In addition to standard corporate tools, UNDP offices implementing Global Fund-implemented projects have developed a number of data collection and reporting tools, both using technologies and involving communities in independently monitoring project activities. Key mechanisms for risk monitoring include:

- Results monitoring and site visits are actively used to identify emerging risks and provide suggestions on required treatments. Risk monitoring is therefore integrated in M&E plans and templates, such as those used to assess effectiveness of interventions, back to the office reports from site monitoring visits, results reporting, etc.

- A complementary and effective approach to M&E and risk monitoring includes the involvement of the end users in monitoring the effectiveness of the interventions and collecting feedback or concerns on the activities. This can be done through third-party monitoring systems, community-based monitoring and surveys, integrated bio-behavioural surveys and/or bio-behavioural sentinel surveillance. For more details on existing practices in offices implementing GF projects, ask your BPPS Global Fund Partnership and Health Systems Team (GFPHST) focal point. Technologies can be used to enhance and monitor access and effectiveness of health services. These carry some inherent risks and risk assessments must be conducted as per checklist in the UNDP Guidance on the Ethical Use of Digital Technologies for Health Programmes to consider ethical, confidentiality, impartiality, access, knowledge risks in the roll out.

- Institutional risks are closely monitored through compliance activities, such as spot-checks, financial verifications, Sub Recipient (SR) and/or Global Fund audits, procurement committees, etc. which are used to gather more information on the risk exposure and plan for corrective actions.

- The UNDP Quality Standards for Programming policy outlines UNDP standards and mechanisms to assure programming quality. At the implementation and monitoring stage, projects are assessed at least every other year on the extent to which risks are identified with appropriate plans and actions taken to manage them. It also verifies whether Social and environmental sustainability are systematically integrated and whether potential harm to people and the environment are avoided, minimized, mitigated, and managed. Risks related to countries under crisis context are also monitored through the crisis risk dashboard.

When is it done? Risk monitoring is an ongoing process, as frequent as project M&E activities. In addition to the annual planning process, project risk reviews are conducted at least once a year, and the results reflected in the project risk register.

Practice Pointer

Risk management in crisis settings

UNDP policies

Global Fund policies and tools for risk management in high-risk and crisis settings are available in the Global Fund Risk Management Framework and tools section.

UNDP has two main policies to guide the response to crises:

- Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) for crisis response and recovery which provide a corporate institutional and operational framework so that critical decisions and actions can be taken quickly in response to crisis situations. The SOP focuses on the relatively brief period between the onset or identification of an imminent crisis and the point when a Country Office has in place the resources to implement recovery and resilience initiatives. The SOP outlines the relationships, responsibilities and communication between Country Office, Regional Hub, and Headquarters, during the crisis response.

- Financial Resources for Crisis Response released by the Crisis Board following a crisis triggering event or by the Crisis Bureau for undeclared crisis situations.

- In addition, in 2017 UNDP mainstreamed into relevant corporate policies a number of fast track measures and some of these provisions can be delegated to the Head of Office by the Regional Bureau or other Central Bureaus and routed through the Regional Bureau.

The UNDP Crisis Response Portal provides all the necessary guidance, templates, and resources for preparing and responding to short or protracted rises. It includes:

- early warning and preparedness measures

- crisis response packages

- port-crisis closure and transition arrangements

- operational measures for crisis response

- Communication and visibility toolkit

- Emergency deployments and UNDP Global Policy Network (GPN) roster

Considerations in high-risk environments

In addition to measures for crisis response applicable to specific UNDP Country Offices (COs) there are additional provisions to consider for Global Fund grants implementation in high-risk environments.

The CO/Principal Recipient (PR) should check with the Global Fund whether the country (or affected region within a country) is classified as a Challenging Operating Environment (COE), which could mean additional Global Fund policy flexibilities are applicable.

The main principle for managing Global Fund grants in high-risk environments is the increased need for UNDP CO/PR to manage risk, document this process and communicate. During grant-making/reprogramming request or defining project stage/grant-making, risks should be identified, and risk treatment planned and reflected in project plans. If the onset of a crisis is sudden, one of the first steps to be undertaken is analysis of risks created by the crisis, and identification of immediate responses required.

By default, implementing grants in high-risk environments means higher risks. The need to continue delivery of lifesaving services calls for agility and flexibility in procedures (both UNDP Fast Track measures mainstreamed in POPP and Global Fund COE provisions) while ensuring sound programmatic engagement and support (UNDP Crisis Response Portal). Since existing procedures are part of internal controls, relaxing them means the organisation is accepting higher risk. According to the standard Grant Agreement, the PR bears all grant-related risk. Therefore, in high-risk environments the PR should consider the following:

- Ensuring uninterrupted services in the high-risk environment may require a change in implementation arrangements, especially if the crisis onset happened after grant signing. In situations of natural disaster or armed conflict the project beneficiaries may be displaced, and a quick assessment may be required to understand how to provide health services in the changed circumstances. Supplying health products to new service delivery spots may require changes in pre-crisis practice.

- Safety risks to project beneficiaries and staff should be carefully examined. This is applicable not only in areas of armed conflict or natural disasters, but also where activities of key affected populations are criminalised. Immediate risk mitigation measures in such circumstances include ensuring confidentiality of beneficiary data, controlled and limited access to records, use of unique identifier codes and partnering with national institutions. Long-term measures include policy work to change punitive laws.

- Communication and consultation as part of risk management is essential in high-risk environments. It is necessary to discuss the risks, causes and impact with Sub-recipients (SRs), and jointly plan risk treatment. It also involves discussing risks with other key project partners at the country level, since common risk mitigation measures may be applied. Finally, it is very important to communicate about risks with the Global Fund and flag any “unknown” areas. For example, in case of armed conflict outbreak in part of the country which prevents access to sites, the Global Fund should be informed about the PR’s inability to access and verify assets in the conflict zone, and the Global Fund should decide if this is acceptable.

- In the given circumstances, can the PR honour the obligations undertaken under the Grant Agreement with the Global Fund? For example, the Global Fund can request that all assets purchased with grant funds are returned to the Global Fund. In situations of armed conflict, the PR should flag the uncertainty related to physical verification and control of assets which will be given to SRs in the zones not accessible to the PR. Other example includes access to service delivery sites for verification of programmatic data.

- Whether the programme objectives are realistic – This is particularly important in situations where the context changes after the grant is signed. The PR should undertake an analysis of assumptions used to set the original targets, and their validity in the changed circumstances. When necessary, a reprogramming request should be submitted to the Global Fund.

- Weaknesses in national systems and capacity is often the main contributor to high-risk environments for Global Fund grant implementation. This is addressed by midterm capacity development measures, aiming to address root causes. In the short-term, mitigation measures can include outsourcing and engaging technical assistance for key implementers. For UNDP-managed grants, in case of weak capacity for financial management at SR level (as determined by the SR capacity assessment) transfer of funds to the SR is usually avoided and SRs implement sub-projects through direct payment modality.